Covid-19: What works in an effective multi-agency response, Part III

This is the third in a series of ongoing reports that aim to understand the current challenges faced by Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) during the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK, with the goal of supporting the ongoing development of good working practice. An introductory report included background information, introduction to relevant theory and overview of the methodology. Report 1 discussed findings from interviews conducted between April 13, 2020 – May 14, 2020; and Report 2 discussed findings from interviews conducted between May 15, 2020 – June 12, 2020.

Through ongoing interviews with responders at strategic and tactical response levels, the research addresses interoperability dynamics at both local and national levels and assesses how the evolving situation affects strategies, practices and outcomes over time.

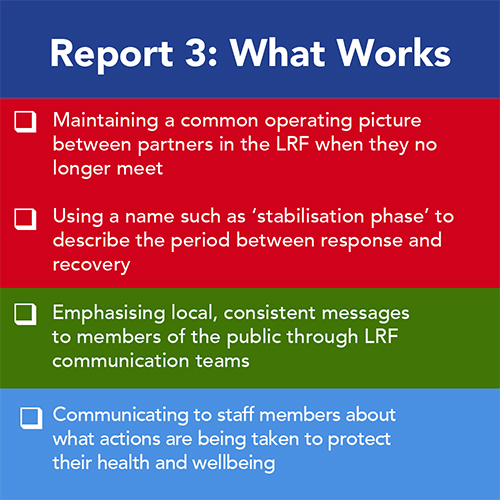

The findings are presented alongside relevant theory to generate evidence and theory-based suggestions of ‘what works’ in the Covid-19 response. We identify four key findings, which are discussed in order, followed by the four ‘what works’ suggestions.

Key findings:

Importance of maintaining a common operating picture between partners within the Local Resilience Forum.

Importance of providing a name for the transition period between ‘response’ and ‘recovery’.

Importance of consistent localised messaging.

Importance of demonstrating respect for staff health and well-being.

Method

Interviews included in this report (n=17) were conducted with 10 different responders, all of whom were included in the previous report. Responders are from police, fire and rescue and ambulance services from across the United Kingdom. Interviews took place between June 12, 2020 – July 27, 2020.

During this period, response activities included: Understanding the impact Black Lives Matter protests might have on the development of Covid-19, for example how large gatherings might affect the spread of infection and how some LRFs were preparing for a potential rise in case numbers because of this; understanding and implementing Test and Trace, for example with some LRFs setting up outbreak cells to manage the localised response to this and incorporating local outbreak plans; responding to further easing of lockdown measures, for example police responders in particular discussed an increase in activity of operational responders due to this; and understanding and implementing the shift from ‘response’ to ‘recovery’ for example, the standing down of Strategic and Tactical Co-ordination Groups (SCG and TCG respectively).

We have included responders from a broad range of geographical locations across the UK, from the North, South, Mid-England and London, as well as responders from Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. However, given the diverse experiences of those in different areas (owing to implementation of local lockdowns), we acknowledge that it is possible we have not been able to capture all of the experiences LRFs are currently facing.

Context – changes in the rules in the period covered by the interviews

On June 13, 2020: In England and Northern Ireland, households with one adult could become linked with one other household of any size, allowing them to be treated as one.

On June 15, 2020: In England, retail shops and public-facing businesses, other than those on the exclusions list, were allowed to re-open.

On June 19, 2020: The UK’s Covid-19 Alert Level was lowered from Level 4 (severe risk, high transmission) to Level 3 (substantial risk, general circulation).

On July 3, 2020: A list of 59 countries for which quarantine would not apply when arriving back in England was published. These changes did not apply to Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland where quarantine restrictions remained in place.

On July 4, 2020: Lockdown restrictions were further eased in England and several businesses in the hospitality sector (including pubs, restaurants, hairdressers, and hotels) were allowed to reopen. Businesses not allowed to reopen included indoor gyms, swimming pools and nightclubs.

On July 10, 2020: Northern Ireland lifted quarantine regulations on arrivals from 50 countries.

On July 18, 2020: Local authorities were given the power to enforce local lockdown.

On July 24, 2020: It became mandatory to wear face covering in shops and supermarkets in England.

Importance of maintaining a common operating picture between partners within the Local Resilience Forum

Results from interviews:

In our last report we described the impact ‘business as usual’ was having on the ability of LRFs to work together effectively with 'conflicts’ and ‘tensions’ beginning to emerge in some LRFs. For example, conflicting pressures were described when work that had previously been stalled owing to Covid-19 was beginning to come back. However, the focus in nearly all LRFs now seems to have shifted to understanding what the move out of this response phase is, and when to step down the SCG and TCG.

A number of responders described challenges in moving out of the initial response phase with members from different organisations disagreeing on when this should take place. One responder commented: “Now the problem is each individual organisation’s sense of ‘we’re there’ is all going to be slightly different.” This responder expanded: “Our partner agencies … seem to have gotten attached to the SCG and want to hold onto it forever.”

Another responder said: “The (Directors of Public Health) are more nervous than most,” and added: “I think it is particularly fear of being left in the lurch without any access to resources or the support it gets from us”.

The reason for this discrepancy was described by one responder who explained: “I think [(he SCG) is a bit of a comfort blanket. If you are the designated Covid lead in your organisation where you have got another level above you, you can go back to your boss and say I need to go back to the SCG because that is where the decisions are made. When you remove the SCG, you are a bit naked then and that might be it … but it is also I think that different organisations are at different levels of normality.”

Another responder explained: “People get used to (the SCG) being around and you can deliver your problem on the day to (the) SCG or TCG and it will get resolved, but that’s not what we’re here for. The responder continued: “If you’re the one carrying the can and got the most skin in the game you’re the one going ‘hang on a second’ … so I can understand why (the Directors of Public Health) are the ones going ‘okay, but is this really the right time?’”.

One responder managed this discrepancy between agencies by asking all members to agree: “The eight things that need to happen to say we’re finished … when these eight points are all met ,we are finished as an SCG.” The reason for this was: “It is easy at the start because … it’s just one shared purpose. But as soon as that goes away, you do get that difference of opinions, which you will get with different agencies and a big group. You have almost got to give them a single focus again to go, those eight points which were your single focus, well we have reached that, so game over”.

This does not seem to be consistent across all LRFs, with one responder saying: (The SCG) came to a natural end because effectively what have now seen is a lot of the Covid-related work has become normal day-to-day work, so like the PPE is almost becoming mainstreamed, so we know we need these large quantities of PPE and our procurement department knows it … it just happens.” Expanding upon this, the responder said: “(The SCG])just came to an end, everyone was clear that a lot of the work was being done or sorted or passed to the recovery cell and they weren’t making decisions there as much as originally.”

One responder summed up the importance of the SCG and TCG staying cohesive during this period: “It comes back to stuff we have mentioned before, communication is key, we have to stay on the same page, we have to have that joint information picture … around risk, but what I am learning here is also a joint information picture around change,” emphasising that: “Information flow is so critical all of the time which is why I am pushing for that central, keep the (common operating picture) alive … there needs to be real clarity around who has got this, making sure it is completely gripped and we all see it.” The responder explained that this is because it is: “To make sure we have got sight of all of the risks.”

Importance of naming the transition period between ‘response’ and ‘recovery’

Results from interviews:

Responders have described the importance of having a name (eg stabilisation or transition phase) for this middle ground between response and recovery to remind members that they are still there.

The chair of one SCG said: “While the SCG arguably remains extant, we just won’t be meeting … so we’ll be there in the background, there is just no real need for it to meet,” and recognised that the Directors of Public Health were more nervous than others at stopping the SCGs: “We have just said to the directors of public health, you trigger (standing the SCG back up again) if your plane looks like it’s going in the wrong direction you can wave and we’ll stand up again, we don’t need metrics to stand us back up again we just need you to say so.”

This responder expanded: “The other alternative is to close (the SCG) down and the message that sends is ‘mission complete’… that sends all kinds of dangerous signals, so the other alternative is to leave it running in the background so it is technically in existence, but there is nothing happening in it.” The responder added: “What we are saying is this is still a very real thing and the SCG is a leadership group of senior people across the partnership, saying this is still very important to us. If we all walk away … what we’re saying is it’s not very important anymore.”

One responder from the same LRF explained they are currently in “unchartered territory” whereby: “Under the current LRF set up you are either in response or you are in recovery … This is different, and we are in something they are calling stabilisation phase, so we’re not quite responding, we’re not quite recovering, we are in the middle … the coronavirus is still here, we are still responding, it is just that we are responding in a different way.”

This middle ground presents challenges for the LRF because: “This is sort of a new one for us really and it is causing a lot of work.” For example, this responder explained: “Because of those conversations about recovery and stand down … (members of the LRF])are getting emailed (from their day job manager) saying they will go back to work on the 31st July, but … no, you’re not going anywhere … we are still knee-deep in stuff over here,” and summed up: “That is where we need this middle ground kind of area called stabilisation.”

Another responder from a different LRF explained they have set up a transition working group, which: “Takes the place of the SCG, it is pretty much the same partners on it … that then becomes a transition kind of recovery type cell and the SCG will be no more … unless a second spike hits us pretty hard.”

Importance of consistent localised messaging

Results from interviews:

A concern raised in many LRFs was around the ability to maintain a consistent shared understanding of the situation, both within the LRF and between the LRF and the local public. This concern was often exacerbated by the input of the media: “We have got whole (communication) cells set up to deliver public messages, but that can be overshadowed by the gut of the press,” noted one respondent.

Responders expressed particular concern around the negativity of reporting: “All (the media) have done is try to dig holes in what the government and scientists have been trying to do to keep people safe. I don’t think there has been anything positive … it is the only thing that people actually listen to and it is very easy to turn the tide just through the media.”

Using the weekend the pubs reopened in England as an example, this responder explained: “The media were doing everything in their power to show large groups of people not social distancing when in reality that wasn’t the case … I think generally people were being sensible and there wasn’t the disorder the police were expecting and I think it is a shame the media can’t report on that rather than on the negative side.”

Another responder said of the media: “They want to talk about the down side of everything, they want to accentuate the bad side of everything.” The responder explained how this has been: “Hugely inflammatory for the SCG and the police,” and described how social media can exacerbate the situation, because: “It is unregulated, unchecked and you seem to spend half your time telling people that it is complete nonsense, that it is not real, and it is really hard work.”

This seems to be heightened in the devolved state of Northern Ireland whereby it: “Depended on whether you switched on BBC news, the national news or the local news and you inevitably get a different message and that did create issues on the ground for people,” according to one responder. But this responder went on to explain it is not causing as much of a challenge now as it did in the early stages of the response, because: “We are not engaging (with the public) the same now, you’re not actually applying power, you’re not challenging people’s location. We’re not asking all of those questions and, as a result of that, the implications have reduced for us.”

When discussing the impact this has on the SCG, one responder explained: “I think that where the little battles are now is the consistency of messaging so that everything makes common sense, because I think where we are getting a bit of grief now, SCG (are) having lots of debates about things that don’t make common sense.”

When describing how to overcome the problem with unclear messaging in the media, this responder explained: “It is just about providing very strong and clear messages that are aligned and can’t be contradicted … it is not dynamic all of the time, so you need to provide a long term strategy to enable you to do your day job as well as keep an eye on what’s going on.”

Importance of demonstrating respect for staff health and well-being

Results from interviews:

Many responders emphasised the importance of recognising how hard staff have worked throughout the initial response to Covid and the need to foster resilience: “Something I’m really mindful of that we have discussed is how tired some of our staff are and how do we balance that out with making sure they are fit and well ready to do Covid again …]where normally some people would be going on their summer holidays and getting their relaxation, but they’re probably not going to be able to do that so I think there is a real difficult balancing act balancing the staff welfare bit.”

Another responder described this as a “perfect storm” whereby they are dealing with: “A spike in demand while trying to deal with a workforce who are tired and haven’t had any time off for four months.”

One responder said: “We’re almost working on emergency footing for the last six months … that is normal business now,” and expanded on this by saying: “Everyone around the table has said they haven’t had a day off in six months and they’re tired … you’re just constantly working on a wartime footing, you don’t have conversations anymore about back to normality because no one knows what normality is like anymore … everybody is absolutely shattered.”

This responder went on to explain: “If you don’t give them down time then you can’t raise your game again in September and October, so that is the main challenge for me is that everybody just needs to go away and recharge their batteries. It’s the human cost, you could run a car 24 hours a day, seven days a week, but eventually at some time you have to switch it off and give it a service.”

Responders highlighted the negative impact this can have on staff: “Some officers … will just stay motivated and just do it … but at the other extreme there are inevitably people who are tired of this and I think that’s fair as well … you have got a workforce who are highly motivated and highly competent, but they are tired and that’s when mistakes are made too.”

This responder explained they have tried managing the situation through increasing the number of staff who can take leave at any one time, because: “People need to know that the people at the top that make the decisions are listening and if the workforce say we’re tired and the organisation responds and says okay we’re going to put the leave up to 20 per cent, if I am an officer in the front line I am going ‘well at least they’re listening’. It is about listening and responding.”

Another responder explained that part of maintaining motivation and resilience moving forward is around making sure reasons behind health-related decisions, for example, regarding PPE, are being shared with staff: “It is just making sure that that information is shared, and being that sounding board for people that feel they may not have the right levels of protection and reassurance and guidance to them, that no (the PPE) you have is exceptional, but when worn correctly it gives you that greater level of protection.”s

This responder went on to explain how webchats have been organised in which staff can ask experts any questions around PPE and personal safety and that these were well received: “There were several questions which were really well worded and got the answers required, which helps because people then go back and word of mouth spreads probably better than a lot of publications.”

The benefit this had on staff was described as: “A huge psychological impact on the basis if they haven’t got confidence in the equipment or in the processes that are there, they will shy away from doing their day-to-day work but if you can instil that confidence in them from an early stage, they then find they can continue to work as normal but understand that ‘I have got this additional level of protection, which works in the way it has been described and demonstrated’.”

Theoretical application

As discussed in this series of reports previously, a shared social identity, ie a sense of ‘we’, rather than ‘I’, can help different groups within an organisation work more effectively together and fosters trust in other group members.

Legitimacy of treatment plays a key role in facilitating identification between groups and can be enhanced through open and honest communication from one group to another. Failure to provide this information can result in perceptions of illegitimacy, which tends to undermine shared identity, can engender conflict rather than co-operation, and can hamper the group’s ability to work together effectively.

One way a shared social identity can improve the ability of a group to work more effectively together is through increased resilience. When people identify with members of the teams they work with, they get more support and are consequently less susceptible to stress, as well as being more willing and able to work together to achieve shared goals.

For example, in the current response to Covid-19, leaders can help maintain a sense of shared identity between group members through providing open and timely information to staff members, particularly around health and well-being, such as encouraging annual leave and providing information about PPE, as well as ensuring a common operating picture among group members. In turn, this could help enhance resilience, particularly as the response moves into a phase of uncertainty around second waves, or what is coming next.

-

Louise Davidson, Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science & Technology, Health Protection Directorate, Public Health England, UK and School of Psychology, University of Sussex, Brighton, United Kingdom

-

Holly Carter, Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science & Technology, Health Protection Directorate, Public Health England

-

John Drury, School of Psychology, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

-

Richard Amlôt, Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science & Technology, Health Protection Directorate, Public Health England, UK

-

Alexander Haslam, School of Psychology, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia

-

Clifford Stott, School of Psychology, University of Keele, Staffordshire, United Kingdom

-

John Drury, Holly Carter and Clifford Stott were supported by a grant from UKRI, reference ES/V005383/1. Holly Carter and Richard Amlôt are funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response (EPR) at King’s College London in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with the University of East Anglia and Newcastle University. Louise Davidson is also affiliated to the EPR HPRU and her PhD research is jointly funded by the Fire Service Research and Training Trust and the University of Sussex. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England.

References

-

Davidson L, Carter H, Drury J, Amlôt R, Haslam S A & Stott C (2020): Covid-19: Recommendations to promote an effective multi-agency response.

-

Davidson L, Carter H, Drury J, Amlôt R, Haslam S A & Stott C (2020): Covid-19: Recommendations to improve effective multi-agency response, Part 1.

-

Davidson L, Carter H, Drury J, Amlôt R, Haslam S A & Stott C (2020): Covid-19: What works in an effective multi-agency response, Part II.

-

Drury J, Cocking C & Reicher S (2009): The nature of collective resilience: survivor reactions to the 2005 London bombings, International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 27(1), 66 – 95.

-

Haslam S A, Jetten J & Waghorn C (2009): Social identification, stress and citizenship in teams: a five-phase longitudinal study, Stress and Health, 25(1), 21-30. doi: 10.1002/smi.1221

-

Turner J C, Hogg M A, Oakes P J, Reicher S D & Wetherell M S (1987): Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory, Basil Blackwell.

-

Stott C, Hutchison P & Drury J (2001): “Hooligans” abroad? Inter-group dynamics, social identity and participation in collective “disorder” at the 1998 world cup finals, British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(3), 359-384. doi: 10.1348/014466601164876

-

Carter H, Drury J, Rubin G J, Williams R & Amlôt R (2015): Applying crowd psychology to develop recommendations for the management of mass decontamination, Health Security, 13(1), 45 – 53.

-

Carter H, Drury J & Amlôt, R (2018): Social identity and intergroup relationships in the management of crowds during mass emergencies and disasters: Recommendations for emergency planners and responders, Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice. doi: 10.1093/police/pay013

-

Reicher S, Stott C, Drury J, Adang O, Cronin P & Livingstone A (2007): Knowledge-based public order policing: principles and practice, Policing, 1(4), 403-415. doi: 10.1093/police/pam067

-

Haslam S A, O’Brien, Jetten J, Vormedal K & Penna S (2005): Taking the strain: social identity, social support, and the experience of stress, British Journal of Social Psychology, 44(3), 355 – 370. doi: 10.1348/014466605x37468