The view from a super recogniser

If you follow the news, it’s impossible to miss the heated debate that is currently surrounding the trial and potential roll-out of automated facial recognition technology by police forces, says Kenny Long. However, the truth of the matter is that the technology is widely misunderstood. People need to be made aware that an individual has not – or ever will be – arrested purely because they have been flagged by facial recognition software.

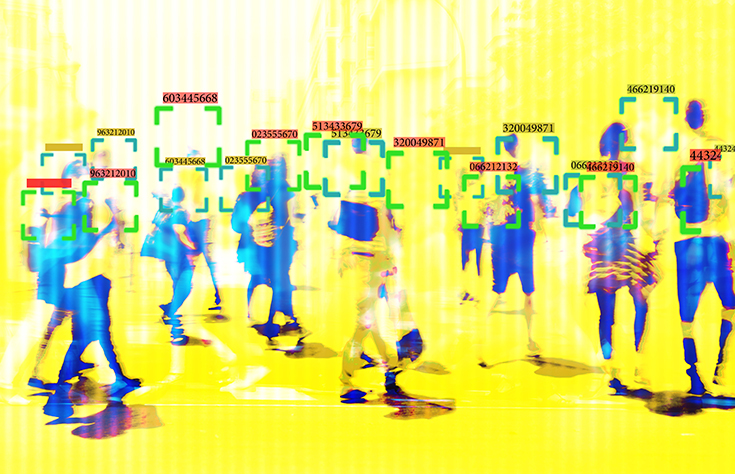

The main misconception surrounding facial recognition technology is that we are entering a dystopian future of reduced civil liberties at the hand of a surveillance state. But the fear that decisions regarding our freedom and rights will soon be made by unaccountable, autonomous machines is unfounded (Andrey Kryuchkov/123rf)

In order to make an informed and accurate judgement about facial recognition technology, you must take into account why it is needed and the benefits it brings, in which circumstances it should be deployed, and why trained individuals, such as super recognisers, will always remain key to the identification process.

The emergence of super recognisers

The term ‘super recogniser’ was coined by academic Richard Russell as recently as 2009. Although it is not a new skill, he uses it to describe: “People with extraordinary face-recognition ability.” It is estimated that only one to two per cent of the population has this innate talent, and it is not yet fully understood why some people can recognise faces so much better than others.

The use of super recognition for law enforcement began in 2013 with the creation of the UK’s first formal Super Recogniser Unit, established within the Met Police by Mick Neville, a former Scotland Yard detective chief inspector. Neville recognised that certain police officers had an extraordinary ability to identify individuals on a watchlist against those in CCTV footage – far more than what was considered an ‘average’ identification rate. He saw the unit’s creation as a way to harness the power of the force’s super recognisers and enhance their skill with technology. His investment into these individuals, a small team of six, proved successful and in 2016 alone they were able to make over 2,500 identifications that led to an enforced outcome, such as a charge.

The ability to spot a suspect has always been an important aspect of the law enforcement process, and the technology of the day had always been used to make this process more efficient. The use of super recognisers, especially when powered-up with database technology and automated facial recognition, is just another link in this chain. Unfortunately, despite its success rates, the Super Recogniser Unit was underfunded and underused owing to caution exercised by the Met incited by lack of understanding about how super recognition works.

Some of the founding members of the Met’s Super Recogniser Unit, myself included, went on to found Super Recognisers International (SRI), a private organisation that offers out the skills of registered super recognisers from across the world. Today, its services are called upon by everyone from private clients to football clubs, and even police forces.

Super-powered humans

Database technology that allows super recognisers to memorise and compare images to CCTV footage rapidly, has already enabled them to perform extraordinary feats, such as identifying the perpetrators of last year’s Novichok attack in Salisbury. So, given the public’s concern about live facial recognition technology, why not stop here? Super recognisers are already doing brilliant work without the help of this technology, and would this not render their talent, and therefore services, redundant?

The answer to both of these questions is a resounding ‘no’. When deployed properly, live facial recognition technology can provide the benefit of a certain level of automation while leaving the final decision regarding what action to take in the hands of a trained professional. Ultimately, the aim of facial recognition is to make it easier for law enforcement to address public safety on a much larger scale, a task facilitated by the skills of super recognisers.

Unlike a super recogniser, AI algorithms, such as those used with facial recognition systems, never get fatigued or make errors in judgement owing to human factors. They can operate around the clock and the more they are used, the more accurate they become, learning and finessing their task constantly.

Think about the immediate response to the London Riots in 2011. While part of the Met Police’s Super Recogniser Unit, my colleagues and I combed through hours of CCTV footage to identify wanted suspects and persons of interest. This would have been much faster if the initial analysis had been carried out by a facial recognition algorithm, leaving us to make the final decision on a much smaller pool of possible sightings. The force would then be able to allocate human resource elsewhere for a more effective strategy.

Why a human is always in charge

The main misconception surrounding facial recognition technology is that we are entering a dystopian future of reduced civil liberties at the hand of a surveillance state. The fear that decisions regarding our freedom and rights will soon be made by unaccountable, autonomous machines is unfounded. Facial recognition is simply a tool that presents possibilities for humans to validate or discard. No facial recognition programme will ever make that decision autonomously – a human will always be in charge.

Facial recognition is exceptionally accurate, but the possibility of false positives will always be a concern – especially in a high stakes industry such as law enforcement. It is therefore imperative to know that the final decision will always be made by a trained individual. This person doesn’t necessarily have to be a super recogniser, but they do have to be trained to use the technology.

The key point to remember is that a machine doesn’t have the ability to arrest, question or otherwise inconvenience somebody flagged up as a possible match. Again, this is a task solely reserved for a trained officer who is capable of viewing the evidence, and any other extraneous factors, and making a judgement call on the next best action. This includes just approaching somebody and asking to see a form of identification, if there are no issues, then no further action will follow.

Working towards effective deployment

In truth, there are currently very few active police deployments of live facial recognition anywhere in the world. This is unfortunate, as the process of facial recognition won’t be improved if the technology isn’t put into practice. The way forward is to encourage proportionate, responsible and closely monitored pilots of automated facial recognition that will allow us to learn what works and what doesn’t – as well as putting people’s minds to rest by reassuring them that its sole aim is public safety.

So, don’t believe the fear, confusion and doubt currently being spread about police use of live facial recognition. The fact is that it’s a highly powerful tool that should be available for use by law enforcement agencies, as long as there is adequate regulation in place. This use of this technology is just an evolution of the role that super recognisers already play, and it will of course only ever be deployed with an accountable human in the driving seat.

Kenny Long is UK Business Development Lead – Facial Recognition, at Digital Barriers

Kenny Long, 30/10/2019