Our public private lives – external and internal conflict

Larissa Sotieva looks at how, in the process of giving up our online privacy, we are actually in danger of making ourselves more prone to manipulation, and examines this paradox within the context of regions affected by violent conflict.

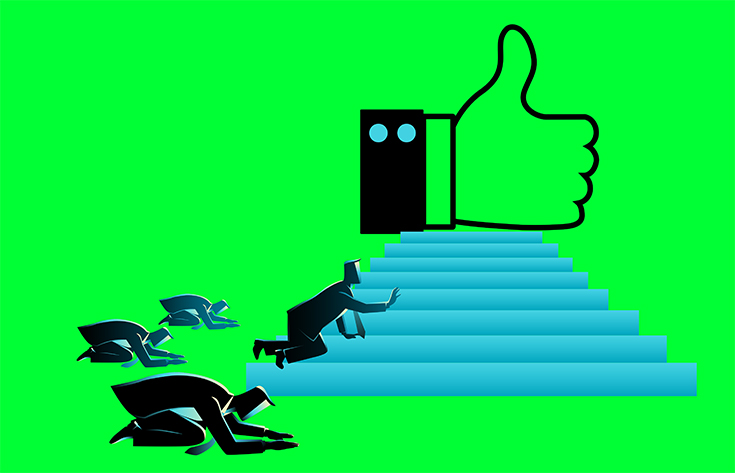

We are willing to spend our time, energy and emotional energy collecting ‘likes’ on social media, while recognising to ourselves that it doesn’t mean anything. But when we are alone, these ‘likes’ do not particularly help us to feel ‘liked’, and we dive into our smartphones again, and so the cycle continues (Image: Rudall 30 / 123rf)

The Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandals around the use of personal data to influence public and political processes have prompted many discussions about the concept of personal space and the right to privacy.

I’ve often heard people express indignation, but noticed that they console themselves with the thought that they have ‘nothing to hide’ and an attitude of ‘to hell will them, let them look as much as they like’.

Yes, most of us are law-abiding citizens and in fact have nothing to hide. But in this case what is the point of privacy? And what do we mean by privacy these days? Has the right to privacy become the lot of just a small group of people? And what is the impact on us of the feeling that somewhere someone knows everything about us – what you eat, where you go, who your friends are, what you watch, do, who you like, etc.

Do we really accept the premise that we have nothing to hide so ‘let them see’ - or are we forced into it, because public opinion has shifted towards the assumption that if you’re not open, then you must have something to hide?

We have completely forgotten that the ubiquitous use of smartphones does not change fundamentally who we are as a species. Despite all the tricks of technology, we remain the same human beings whose fundamental sense of security is based on recognition and group belonging, as well as the ability to hide from prying eyes when we need.

Privacy is a basic biological and social need. Research conducted with survivors of the Nazi prison camps revealed that the most prevalent cause of suffering in the camp was the complete lack of privacy and the ability to be alone by oneself.

Our ancestors hid in caves, or built houses to protect themselves from all dangers, including from their own kind. Today, when for many of us there is no obvious physical danger to hide from, we still prefer to live behind closed doors, but at the same time are willing to share publicly what goes on inside the house.

Humans are remarkable creatures – we can hide from our loved ones something that we so easily share with strangers, even with a large audience of strangers. There are many explanations for this, but I will focus on one that has a therapeutic effect: being unable to establish quality relationships with a few people close to us, we switch in favour of quantity, and attempt to replace our need for stable trusting relationships by surrounding ourselves with a large circle of people.

This brings us a temporary sense of social validity, recognition and reassurance that all is well; the mindset of ‘so many people are with me and they are all my friends’.

We are even willing to spend our time, energy and emotional energy collecting ‘likes’ on social media, while recognising to ourselves that it doesn’t mean anything. But when we are alone, these ‘likes’ do not particularly help us to feel ‘liked’, and we dive into our smartphones again, and so the cycle continues.

But human coping mechanisms are cleverer than we might suppose. Even in such an exposed arena as social media, we have been quite creative in the way in which we seek social recognition while preserving our natural need for privacy by being selective in what we reveal and want to be seen by others.

Yet often, what we share with the outside world does not necessarily reflect our reality and it is these contradictions which have become a serious source of conflict. By putting a false reality out there, we invented a mechanism for manufacturing ‘fake’, which subsequently became the new social norm.

In parallel, the concept of ‘fake news’ has appeared. Yet for some reason that surprises us, and we are quick to condemn, although this is the same mechanism through which we fabricate our own lives – through carefully curated posts about our interests, activities, shares and likes – albeit on a different level, with fake news relying on our predictable responses to manipulations of contradictions in our worldview.

It is an interesting paradox, that the very mechanism we use to shore up our sense of individual identity and feeling of recognition is also a platform for manipulation and strengthening of our sense of belonging to a group, snuffing out our ‘individual’ thoughts – yet we subject ourselves willingly to it.

But how does all this play out in those regions affected by violent conflict?

The international community is making great efforts to transform conflicts around the world and prevent new ones from erupting. Social media as a tool for working with conflict is often discussed, but my deep conviction is that in order to use a mechanism or tool, first you must understand how it works in a conflict situation. There are many studies on the impact of social media, but I’m interested in how this encroachment on privacy or the lack of a sense of privacy is impacting on efforts to reduce tensions in conflict regions and processes of restoring confidence between conflicting parties.

In societies affected by conflict, people are overly interested in each other's opinions about what is going and in sharing their analysis and predictions with each other. This creates a discourse among themselves, binding themselves into a thought community, which also has an emotional aspect, giving a sense of belonging, support and strength. This thought community then becomes the source of discussion about the future of the conflict, but in the process, the diversity of individual perspectives gets lost in favour of group opinion and interest.

Having the feeling that we are being observed by the other side with whom we are in conflict increases our sense of group cohesion and belonging, even if as individuals we might not fully share the group’s values.

In reality, the lack of privacy – or the lack of ability to speak out and hold an opinion without fear of group backlash – violates one’s sense of freedom and freedom to choose. Accepting that we are being watched is already regulating our behaviour, making us more predictable and controllable. The less privacy we feel we have – the more public our lives are – the more likely we can be manipulated.

Being active on social media does not necessarily facilitate conflict transformation. Indeed, on the contrary – social media could be responsible for forming new conflict groups, this time in virtual reality.

There need to be multiple channels of creating alternatives to war in regions affected by conflict, including the creation of alternatives to mainstream discourse. This includes valuing the opinion of individuals, those with unblemished reputation, broad social capital and leadership potential who can distance themselves from groupthink and offer independent analysis.

People who articulate different opinions, even if they seem unrealistic from our subjective point of view, should have the space and opportunity to do so, at least to set an example for others whose ideas may be more realistic, but are wary of speaking up against the flow of public opinion.

Larissa Sotieva, 20/03/2019