Resilient 2050: The societal challenge

In late 2015, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) ran a resilience essay competition on the theme of Reslience 2050: A blueprint for the future. An international sub-category of this competition was supported by Crisis Response Journal; the overall winner and the winner of the CRJ sub-category will be published in the next issue (11:3).

Here, we present the runner-up, in which Philip Wood, MBE, MSc, Head of School, Management and Professional Studies at Buckinghamshire New University in the UK, examines how resilience in 2050 will require aspirant societies, governments and organisations to balance a multitude of varying, conflicting and competing ideas, ideologies, motivations and causes for thoughts, ideas and action while the complications of our environment seemingly continue to multiply. This paper discusses ideas around the influences that may engender or initiate change and thus inform the shape of risk and impact landscapes.

(Image: Rinosario/Shutterstock)

The future of the world relies on technological development among other factors. While that future may be a technological nirvana or nightmare, the potential overriding resilience challenge to society is likely to be its demographic profile. This societal driver, as much as any potential conflict or unplanned for disaster or catastrophe, will itself shape society’s capability to respond to it. Furthermore, with varying, conflicting and competing ideals, ideologies, motivations and causes for thoughts, ideas and action, complications and vagaries of society continue to multiply. Therefore, the effectiveness of societal continuity will be as much about human as it is technological interaction. Divining and defining what the Resilient 2050 will need to be requires a commensurate recognition of influences and actions that may engender or initiate change and thus inform the risk landscape.

In considering how it will get there, the successfully resilient society of 2050 will need to understand that what happens en route should not be a surprise. An objective view of 2050, and its profile; necessitates a realisation that evolution as well as revolution can lead to environmental and societal change. The acceleration of the realignment of the world in recent years, and perhaps the legacy of over-exploitation of resource – human as well as material – provide clear indicators about the shape of the future and our resilience. Taleb (2010) offers the Black Swans: the ‘over the horizon’ issues that forecasting fails to see. However, equally, there are issues that societies should at least be able to discern against the background of the horizon even if they haven’t seen the colour of their ‘feathers’ before.

In this context, Resilient 2050 is a society that is flexible in thought and practice. It is born out of changed historical legal, governmental and behavioural practices and understandings and of the social developments that are accelerated by technology and humanity. However, reaching that resilience accepts not only that issues are recognised, but also an understanding that in the starting state, the present, society should keep pace with incipient changes that will have matured by the middle of the century.

In discussing water infrastructure, Ezell (2007) said: “Vulnerability is, (therefore), a condition of the system and it should be assessed within the context of a scenario.” Looking at the idea of what is considered to be the future shape of the world, it is pertinent to consider that although prediction and analysis of future risks may be difficult to conduct with accuracy, there are plentiful theories and views. Bias, sensationalism and political and ideological aims will be behind many assessments and intellectual analyses. However, there are particular potential issues that should be considered without going too deeply into the accuracy and detail of prediction or scenario; with enough indicating points of reference to be able to at least reasonably consider these within our assessments of future and emerging risks.

First change – the popular v oice

In some sectors of current society the ability to control and govern can be seen to be at odds with the aspirations of democracy-based populations. Meiklejohn (1948) examined the dynamic of ‘the rulers and ruled’ with a sense of clear frustration about contemporary realities and the inability of the people to be heard. In 2015, populations have finally found a voice, although with global connectivity the voice is contradictory, multi-layered and confusing.

It is probable that the challenges that this voice raises today will be much more vital in 35 years’ time. Social constructs and political decisions in 2050 may be influenced by the popular collective whose thoughts, ideas and values will be centred on the personal and the self and seen through the lens of mainstream and social media; an aspect of modernity that Keen (2012) considered to be a divisive influence.

Mainstream media is currently a prime formulator of thoughts and ideas and has significant influence upon popular and governmental opinion. Phenomena such as the migrant ‘crisis’ in Europe from mid 2015 onwards, seen through the media lens, are quickly brought to public attention with resultant perceptions and campaigns influencing response decisions in real-time from the public. While it is difficult to see where the technology of the future will be able to make news and image transmission much more immediate than it is now, the continued influence of media thoughts and images on societal behaviours will be significant.

However, it is unlikely that TV, radio and print press will be so relevant in 2050. Social media will not be in the form it is currently and has the potential to become untrackable and uncontrollable, with individuals rather than organisations becoming our prime influencers. It is therefore reasonable to expect that media will be much more in popular hands. This has significant implications for government and societal cohesion; although importantly, social media is now facilitating a real change in political participation: “Although younger people pay less attention to political news in traditional media than older people, they simultaneously are more frequent users of social media for political purposes,” said Holt, Shehata Strömbäck and Ljungberg in 2013.

The voice is louder than it ever was, developing from something that central governments have steered throughout history; and for the first time we now have an enabled and connected population that is able to make its own mind up and discuss what its own mind is. In the 20th Century those who ruled could avert their eyes and cover their ears. Rheingold’s (2007) ‘smart mobs’ may perhaps offer a misnomer for the connected future; it may be preferable to think of ‘smart government’; in 2050, a resilient society will not only listen to, but embed the popular voice in governance.

Although the indicators are clear now; the behaviours of the societal shapers of 35 years’ time are less so. Even if it were possible and desirable to stifle the enshrined and legal right of populations to speak and express themselves freely; the ability to do so – even by censoring the Internet – will, in 2050, have been negated by the behavioural and learned approaches of those who are now young children. Our children are encouraged to link, communicate and interact, to express themselves freely and openly using the media voice that has not been available to previous generations. This engendered behaviour will gestate into an innate need and requirement to remain constantly linked, and to have the opinions that they believe are as valid as those of everyone else around above and below them both listened to and acted upon. Bartlett, Miller, Reffin, Weir and Wibberley’s concept of Vox Digitas applies now; in 2050 it will be vital; with the likelihood of the popular voice driving rather than responding to societal restructure.

Second change – who and what will we be?

Where connected society lives, and how it lives, is also a factor for the Resilient 2050. Whether or not inner cities will be populated by low income under-levels with a grown ‘street’ population of the unemployed, homeless and illegal immigrants, the future urban environment will continue to be formed by its populations.

The continued influx of migrant and transient populations into the UK will lead to an even more diverse society in 2050 (Image: Higyou / 123rf)

London is an obvious example of a metropolis in the West that is formed by population, and given current trends and patterns its diversity will doubtless continue to grow. The London of recent years has increased its now fluent and diverse population; and the continued influx of migrant and transient populations into the large metropolises in the UK will lead to an even more diverse society in 35 years’ time; the majority of that society will not have a common language or cultural belief set.

This acceleration of multiculturalism and diversity, if it continues (and there is no reason to assume that it will not) will mean that the flawed concept of ‘British’ cultural behaviours that so exercises our current government (first used in a counter-terrorism context) will no longer apply; if it ever did. Another significant element and aspect of this discussion is a perception that, if the continued growth of large communities based upon migrant populations also continues, then the proportion of unskilled residents will also increase. This may lead to a dispersal of high-level talent from core cities and towns; and that the focus of our metropolitan activity will be on the provision and development of service industries and low-level, low skilled manufacturing with enclaves of business, economic and multinational organisations operating independently of resident populations.

What will remain in our cities in 2050 will provide the challenge and context for the resilient society. For those outside the enclaves, the multiple cultures, polylingual and sectorised communities will continue to grow and increase, with struggles for survival in a burdened welfare state bringing continued black and grey market activity, crime and conflict. Wilson (2012) stated (in a US context) that: “…long-term welfare families and street criminals are distinct groups….they are part of the population that has, with the exodus of the more stable working and middle class segments, become increasingly isolated socially from mainstream patterns and norms of behaviour.”

He also noted that this change has happened in recent decades; the consequent and logical extension of this is that further entrenchment along such themes is probable, and likely to be inevitable globally. When populations do become ‘isolated socially’, societal security and resilience can be compromised.

The tensions exemplified by the London and national riots of 2011, where the pretext of policing failures led to mass criminality by a uncontrolled but technologically linked adversarial force, will not decrease as the strains on metropolitan centres increase, and the gaps between wealth and poverty continue to widen. Recognising the fact that challenges are not ‘faults’, but the result of multiple social changes that result from historic, governmental and individual action will mean that society can reconfigure accordingly.

The indicators of this large-scale change are here, with the demographic of the West changing more rapidly than ever. The recent and continuing phenomenon of immigration and migration from conflict or for economic reasons is continuing. While the basis of immigration in the 20th century was the importation of labour to support national industry, future patterns will increasingly be based upon individual aspiration and the search for stability. This does not necessarily and exclusively infer that immigration is linked to seeking refuge; and it may be illegal and unmeasured. Migration Watch (2010) estimated the illegal immigrant population at 1.1 million, stating that: “It is very likely that, in the five years since that estimate was produced, the number has continued to increase.”

Further extrapolation of those figures and the clear increase in numbers of migrants from conflict zones indicate that the future shape of society will be much changed. While undoubtedly reaping the benefits of a multicultural and work-hungry societal influx, society will also need to be configured and prepared to welcome, absorb and accept that change. The (resilient) society that attempts to accommodate all aspects of a multicultural influx on the scale that can be reasonably expected will need to be conversant with the idea that a resilient society remains flexible and malleable, and able to assume a new collective identity. An inability to absorb and cater for the national and diverse identity of current minority communities will cause our society in 2050 to falter and fail.

History has recent lessons. The riots that took place in Northern England in 2001 exposed a deep social divide that had developed unchecked for generations. The children of immigrants refused to face poverty, intimidation and a submerged identity and confronted the society that could not integrate them. Fifteen years on, some of the seeds of confrontation and division may have grown into the radicalisation and fundamentalist Islamism that fuels terrorism and threatens to challenge our society now and in the future. That, in turn, further fuels right-wing extremism to counter it. Hussain and Bagguley (2005) researched the issue of found identity within the communities that were at the centre of the unrest: “Even recognition of Islam was limited to claims for tolerance and freedom from harassment. This is a demand for ‘recognition’ rather than ‘integration’.”

Ten years on, and among the more extreme elements; the demand is more pressing; with the demand for recognition (another voice to be heard) being more urgently and threateningly pressed. Integration may matter less. To add to the complexity, analysts such as Thomas and Sanderson (2013) consider that the issues not only lie with the division of society from the cultural minority point of view, but also from the viewpoint of young white people (who will be beyond middle-aged in 2050): “The political and media discourse of community cohesion has been regarded as a racialised agenda in two senses. Firstly, it appeared to interpret the ‘problem’ of ethnic segregation in relation solely to Muslim communities. Secondly, it discursively constructs ethnic and cultural tensions as ‘the problem’, rather than as symptoms of deeper economic problems.”

Resilience in 2050 will therefore not only be challenged by popular voice, but also by what that voice will be saying about our traditional and rapidly changing norms and mores of national identity and culture. Most importantly, it is crucial to understand that forced, rather than developed cultures, will not be workable or manageable.

Third change – we cannot govern

To further complicate a challenging scenario, even now there are indicators that governmental frameworks will be transformed by 2050. The growth of consensual decision-making has the potential to devolve central government into regional constructs; with the Scottish aspiration for independence indicating the direction of travel. Boggs (2012) asserted that there is: “.. a perpetual shrinkage of politics as citizen participation, public discourse, and social governance erode.”

It is thought that in 2050, whether traditional politics and politicians have the automatic right, mandate and authority to govern, could be questioned (Photo: Catherine Bebbington/Parliamentary Copyright)

Communication and mutual influence are aspects of a wider manifestation in younger generations of disregard for the concepts of national identity and the lines of governance drawn by central governments. A more social, consultative and collective approach to government and self-determination will probably need to be embedded by 2050. As the shape and attitudes of electorates shift the perception of authority, the acceptance of it will shift in parallel.

The generation born in the third quarter of the last century is probably the last to fully accept that politicians (and the parties that they represent) have automatic right, mandate and authority. Later, current, generations question and expect reasoned and rational answers where explanation overcomes direction. The politics of a resilient 2050 will recognise this, and the fact that enforcing authority without rationale will not be workable.

Linking the cause and effect, there is no doubt that the power of the interconnected voice has had a significant impact upon the traditional view of politics. It is becoming apparent even now that the system of tripartite politics that has dominated UK political scene for the past 200 years is in jeopardy. While Parliament – fragmented it may be – will remain as the arbiter of democratic activity within the UK; what constitutes it and the UK itself will reflect a collective desire of self-determination that can only continue to grow.

The impact of the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum, imbuing confidence in regions and provinces around the need and ability to decentralise governance and government, will be clearly felt in 2050. The resilient 2050 will be challenged if it cannot configure.

Fourth change – belief shift

Alongside societal behaviours, it is useful when thinking of the future to consider beliefs, in particular the shrinkage of active engagement in the Christian religion, and its contribution to the fabric of society, The British Humanist Society provides a summary of censuses and surveys that have taken place over recent years; illustrating a general decline in religious practice among the UK population. While this in itself may not be a concern for the majority who may now focus upon the more acquisitive than the spiritual, the effects may well be felt much further in the influence upon societal mores. This decline may slow; however, the loss of religion’s influence within a particular sector of the community will be challenging to recover.

The society of the future will inevitably be less focused upon the underpinning Christian values of which there are still vestiges today; and the recognition and accommodation of a wider religious palate will have an effect upon society at all levels. Wilkins-Laflamme’s 2014 study of religious polarisation considered that: ‘‘The religiously committed group not disappearing into nothing but rather stabilising at lower levels in regions where religious unaffiliation has been on the rise for many decades could have important implications for social relations and policy.”

The importance of time in this discourse is crucial; the degenerative loss of belief will evolve rather than strike at once; with religion as a unifying force whose decline will leave a vacuum.

It is straightforward to discern what will replace failing Christian values, with Islam continuing to grow in influence and footprint. Per se, one religion is no more influential than any other. However, the emergence of Islam as a growingly influential religion in the UK illustrates not only that the proportion of the population that practices it is growing, but also that its influence will be felt at a societal level.

As with Christianity before it, the influence of Islam will be felt in law, government, entertainment and the media. It may or may not be a negative aspect of society; however it should be considerably decoupled from an automatic linkage and the current preoccupation with terrorism. In the future, what we believe in and stand for as a nation and society will be changed by the balance of our religious beliefs, and the resilient society will understand and accommodate this issue by anticipating it now.

Fifth change – what supports us

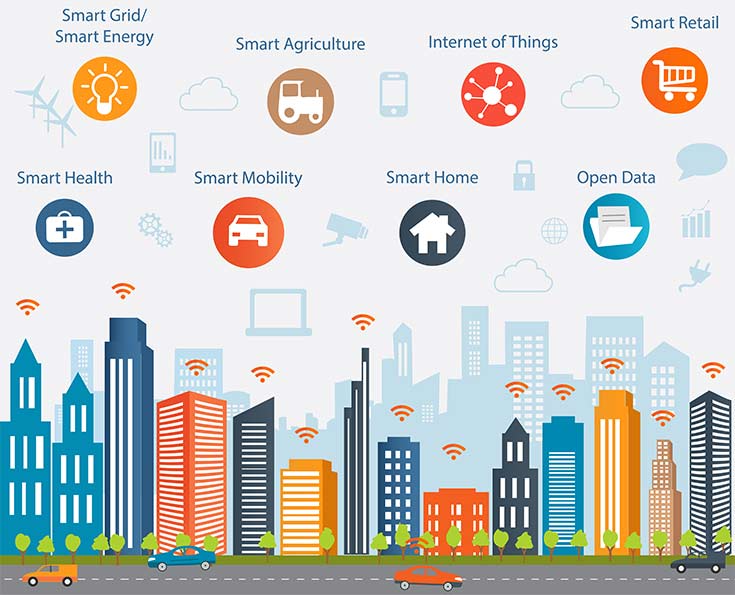

An assumption that currently supports western society, continuity of infrastructure, will have been thoroughly challenged by 2050. The Internet of Things (IoT) will be 35 years old, and will have been developed to a high degree; it will also have been hacked, scammed, disrupted and degraded rendering, for example, some components of the Smart Cities concept less than achievable.

By 2050, will some elements of the Smart Cities concept have been degraded? (Image: Monicaodo/Shutterstock)

It is a sensible and realisable ambition to link our technology, systems and infrastructure. The interface of humans and their relative contribution to the overall and future capability of the web is an important vision. Time, effort and speed of information and data movement will change, an inevitable development of the use of machines to replace and support human thought processes.

In terms of security, resilience and societal continuity, the interconnectivity of human beings brings risk where computers are involved. It is an absolute indicator of the human condition and the constant need to think and consider more expansively that we now move from the mundane and accepted structures of the Internet into the next challenge, which may well be the IoT. But it is important also to understand that while this will bring particular issues and problems, the exploitation of knowledge and capability gaps by determined adversaries – the now more traditional cyber security – will have a continued and continuing damaging effect long into the future.

The prevalence of damaging attacks on advanced systems is exemplified in reports such as PWC’s (2015) where: “90 per cent of large organisations” suffered a (cyber) security breach. A connected, developed and capable infrastructure such as the IoT will be no less attractive to adversaries 35 years from now.

If future networks are fragile, or at least at risk, there is a second and complementary element. Dependence on technology relies on power and logistics; global warming and resource shortages may render our 2050 infrastructure fragile. However, premonitions of impending doom may misrepresent reality and when interventions can be made, the interconnecting links can be effectively broken, or at least addressed in part.

The view that one risk can have a domino effect was taken up by the ‘oil-shockers’ who believed that the eventual loss of oil as an energy resource would initiate a total collapse in western society and its associated values.

A concept of ‘overall societal contraction’ should excite interest as we consider 2050, even more so when considering the problem of: “Emotional, cultural and political catharsis,” Heinberg (2007). Resource shortage events, either temporary or long-term, causing problems at the point of loss, may also affect supply chains and operations through consequent shortages.

In the longer term, social change may also be an issue as market demand and values change to accommodate adjustments in supply. Taken to a more extensive and long-term conclusion, there is significant analysis and study to be conducted on the longevity of economies when pressured by the results of natural events.

The 2007 (discussed in the Pitt Review) and 2013 floods in the UK provide an example of logistical risks in the event of severe weather. In both events the disruption of supply lines to food distribution centres began to cause panic buying in the very short term. The logistic fragility of a system of food distribution, which is node-based and involves distribution of bulk consumer goods by road, was illustrated, evident and clear.

As a further example of fragility while the destruction of transport routes is in itself an issue should they are blocked, degraded or destroyed as a result of natural events, the disruption of logistics routes for the delivery of fuel has its own effect. The threatened fuel tanker drivers’ strike of 2012 resulted in panic buying, creating shortages. The consequential effect was that fuel supplies were reduced at the point of sale. The further impacts on employee mobility were immediate and inevitable. The need to anticipate the longer term effects is a key element of structuring a resilient society that can continue to operate and function where perhaps more is needed to stabilise societal anxiety than ‘advice to motorists’ (UK Government 2012).

The effect by 2050 of a fragile technology base that is underpinned by a resource-hungry power system that may not be easy to feed may be the most catastrophic of all concerns. With the expectations of society underpinned by communications, and economies supported by the need to process, manage and inform, this fragility will coalesce the challenges into a more coherent threat.

Critical infrastructure in 2050 will extend beyond components listed in the UK Strategic Framework and Policy Statement. Our infrastructure will extend to everything that supports society, and in 2050 the impact on a population that must communicate and interact, but cannot do so, may bring much more than moments of quietness.

While the connectivity and sheer power of the networks that support national infrastructure offer a deep and long lasting capability that has the potential to be extremely well-developed in 2050, the fundamental threat of reduced resource and determined adversaries places the unprepared in a tenuous and precarious position. It is important also to realise and determine that guidance that may be in place now to mitigate converged risks may need to be reconfigured as dynamics change. Will the risks exemplified by the UK Government, for example in 2012, be equally pertinent in 2050?

Resilience to the Changes - Circumventing and removing barriers

Thinking about the future challenges, those who wish to predict its risks have to distil theories and research protocol into an analysis of readiness to mitigate impacts. In the context of this paper, patterns and precedent indicate that unless there is a total change in psychology, human need will shape the future. The developments of the closing years of the 20th Century have rolled over into the 21st, and the shape of our current world is in a state of constant flux as the speed of technology, and human response to its pace, continue to influence progression or regression. The shape of the future world cannot, however, be accurately defined, as the variables that will develop as the result of the human and technical developments that continue to accelerate may confound parameters of prediction and mitigation.

By 2050 we will have become accustomed to the interconnected and amplified digital voice (Digital Storm/Shutterstock)

Because of the inherent fluidity and dynamics of the issues raised here, the circumvention or removal of the ‘barriers’ to resilience is essentially neither a realistic nor achievable option. The tide of change that is shaping the society of now and that may crystallise into the basis of society by 2050 cannot be stopped. However if that society is to have resilient function, it should avoid become transfixed by what Barnett and Pratt (2000) term ‘threat rigidity’. To go further, it should not consider these societal traits to be barriers at all, rather they may be seen as opportunities to recognise how to rebuild and reconfigure. Our governments, organisations and structures of state must mitigate rather than vacillate, and address rather than politicise or demonise the issues.

By 2050 we will have become accustomed to the interconnected and amplified individual voice. This voice will have changed the way that national structures, law and order and instruments of authority are viewed. Minority cultural groups will no longer be minorities; and even those that are less powerful or represented in society will be connected, and demand to be heard. The voice of the young will have overtaken the authority of old, with a clamour for democracy in a new sense. Failure to understand that will threaten a corroded national identity and fractured society that will make current ‘problems’ pale in comparison.

Is it reasonable to assume then that the Resilient 2050 is an impossible dream? The converse is probably closer to the potential reality as a resilient organisation should be built on an ability to absorb shocks and impacts, and recover from them. None of the observations made in this discussion are shocking, new or contentious, and by recognising and discussing them there is fair warning of the potential effects and impacts. Therefore, it is essential to begin the mitigation process now but not in terms of 2015.

In 2050, the interconnected and vocal aspirational teenagers of today will be running the resilient society (even for them their time may have been and gone). Unlike those who read and write the future based on the past, they see and understand things differently. Our children are immersed in the connected, multicultural and self-focused, and it is not alien to them – only to previous and older generations. The multi-layered society that may be seen as a resilience challenge is an opportunity for the future and in 35 years the values and mindsets that inform thoughts and attitudes now will be as outmoded as the Victorian mindset is to us.

Therefore, we should see that there are few barriers to resilience and few real problems to circumvent and that cannot be addressed. That idea implies that problems exist that must be overcome. The sole barrier to resilience lies in the framework and silo thinking that characterises much of our approach to the future. Valikangas (2010) espoused the view that setting strategies and associated frameworks limits resilience. Strategies cannot be built or defined on undefined analysis. The embracing of change and the acceptance of societal development offers the key to the resilient future and to be prepared for it involves understand that there will be risks and gaps that require a change in attitude and approach. An espousal of systems, structures and frameworks that deny dynamic change will court disaster and bring significant mental and physical blocks to resilience. By 2050, those who have been comfortable with frameworks will have had their time, supplanted by a flexible and dynamic resilient society, and one with a good chance of longevity and prosperity. Despite the gloom that tends to accompany looking ahead, the society of 2050 has the potential to develop into the most settled and peaceful society for generations; it is the responsibility of those who shape the future to understand that the future is here now and that people, rather than technology, are shaping it.

Sources

-

Taleb NN (2010: The Black Swan (Revised) London: Allen Lane.

-

Ezell, BC (2007): Infrastructure Vulnerability Assessment Model (I-VAM), Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 27, 3, pp. 571-583.

-

Meiklejohn, A (1948): Free speech and its relation to self-government; The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd.

-

Keen A (2012): Digital Vertigo: How Today's Online Social Revolution Is Dividing, Diminishing, and Disorienting Us, London, Constable.

-

Kristoffer Holt, Adam Shehata, Jesper Strömbäck, and Elisabet Ljungberg (February 2013): Age and the effects of news media attention and social media use on political interest and participation: Do social media function as leveller? European Journal of Communication 28: 19-34.

-

Rheingold H (2007): Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution, Cambridge MA, Basic Books.

-

Bartlett J, Miller C , Reffin J, Weir D, Wibberley S (2014): Vox Digitas – Social Media is Transforming How to Study Society, London, Demos.

-

HM Government Prevent Strategy 2011, UK.

-

Wilson, W J (2012):The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press.

Philip Wood, MBE, MSc, 11/02/2016