The challenges facing crisis management

The Covid-19 crisis is not an unprecedented or unpredictable event. Roger Gomm considers the difficult tasks ahead for crisis managers and asks: What lessons should be learned and what strategies can we use to move forward?

Emergency planners were all aware that a pandemic could happen – even that it was likely to happen at some point – but they could not predict when. However, the impact and consequences of such an event would likely be catastrophic – predictably so.

Consequently, policymakers should have listened to prior warnings and should have taken steps to develop a strategy and plan in advance. This could have helped to avert or mitigate the incident.

Crisis managers are strategic leaders and all strategic leaders have to expect to manage a crisis at some point. So let’s start by unravelling what ‘strategic’ means in the context of the core function and purpose of strategic leadership. To be useful, the solution should be something that helps you organise your mind on your way to the control room and that gets you over that: “What should I do first?” moment. You will want to know where to start and what to do first, in order to get some sense of control and give people the leadership they need.

Understanding strategy as meaning situation, direction and action (SDA) is a really useful tool. SDA is a handrail which will guide you to a first move, and then onwards. It is the first tool that incident commanders should consider.

In terms of incident management the core functions are:

Situation - establishing what is happening and what it means…

Direction - defines what we are trying to achieve and involves the strategic aim, enabling objectives and desired outcomes

Action - making decisions, reflecting on outcomes, deciding next steps and maintaining momentum/assurance

Situational Awareness

Situational awareness is achieved by having an accurate understanding of what is happening around you and gauging what is likely to happen in the near future. This has become part of the vocabulary since JESIP, and before this in the UK. The key points are that situational awareness is predictive (at least potentially), it is about getting ahead of the problem, it is very dynamic and, although it exists first in the team members’ minds, it can be represented visually in a common operating picture.

When I am teaching, I explain this process and use it to suggest a strategy. I also make an assessment of the situation using scale, duration and impact (SDI) methodology to help consider the situation in its wider context and assess the potential severity of a given risk or an emergency.

Scale, duration, impact

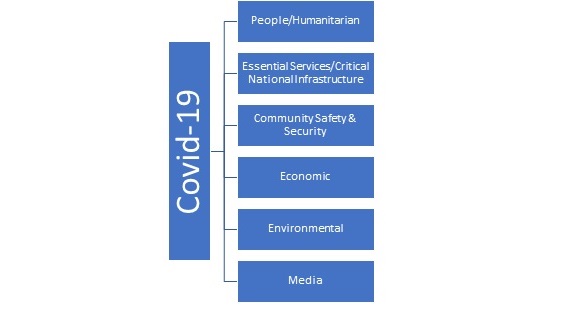

When considering the situation, first look at the scale. How big is it? How far, in terms of geography, might the incident or crisis extend? Next, think about the duration – how long the situation might last in terms of acute, chronic and legacy impacts, or response and recovery. Finally, with regard to impact, look at what the situation is doing to whom and where. It is often easy to identify the immediate consequences but tracing the wider impacts can be extremely difficult. The start of the impact analysis is in the diagram below:

Governments’ crisis management

For the second time in this year, England’s population is enduring a tiered set of restrictions aimed at curbing coronavirus from Thursday. They are not alone; millions in other UK nations and the UK’s European neighbours face similar measures.

The costs to jobs, livelihoods and to mental and physical wellbeing will be hard to bear once again. However, thousands of lives that would have been lost to Covid-19 will be saved. In my opinion, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has taken the right decision – though, as in March, it has taken too long to reach this point.

Five weeks have passed since government’s scientific advisers urged ministers to consider a two or three-week circuit-breaker lockdown to slow a surge in cases. The prime minister did not do nothing. He preferred a regional, tiered approach which was, when conceived, a valid attempt to constrain the virus while avoiding imposing tight restrictions on areas with low infection rates.

However, as so often with the UK government’s management of the pandemic, this strategy was undermined by delays and fumbled implementation. It took three weeks to unveil the plan after advisers first pushed for action. Financial support for businesses that were forced to close in high-risk regions was lower than that previously offered nationally, creating resentment and friction with local leaders. The test and trace scheme, vital to a successful locally-targeted approach, unfortunately proved unequal to the task.

In my lectures I discuss the different types of incidents, recognised as: incident, major incident and crisis. Rittel and Webber, (1973) introduced the Hierarchy of Events: Tame problems; loosely structured; and wicked problems. The wicked problems perhaps describe the current incident management challenges; multiple ‘centres’; inability to respond; lack of information; rapidly degrading conditions; high time pressure for response; inability to prioritise; and no win situation.

In terms of incident management, I believe that there is no such thing as a random event. There is almost nothing in nature that happens spontaneously. It is often the result of a failure of a process and it often develops over time. By claiming that something happened suddenly, what is really being said is that its development wasn’t noticed. In fact, the chances are that the organisation (in this case the government) was aware of the problem or vulnerability, but did nothing about it.

Policing

It has been a turbulent time in the UK and globally – for society in general and policing in particular – with a significant focus on police legitimacy in relation to the use of force, racial discrimination and community relations.

In addition to the critical services that the police provides, the Covid-19 Regulations have added another layer where policing has to deal with non-compliance, illegal gatherings, parties and raves with serious implications for staff’s health and safety.

An additional effect has been that the police have had to manage a range of protests: Black Lives Matter; Extinction Rebellion; anti-vaxxers; conspiracy theorists; and others. This has affected resource availability and occasionally led to disorder.

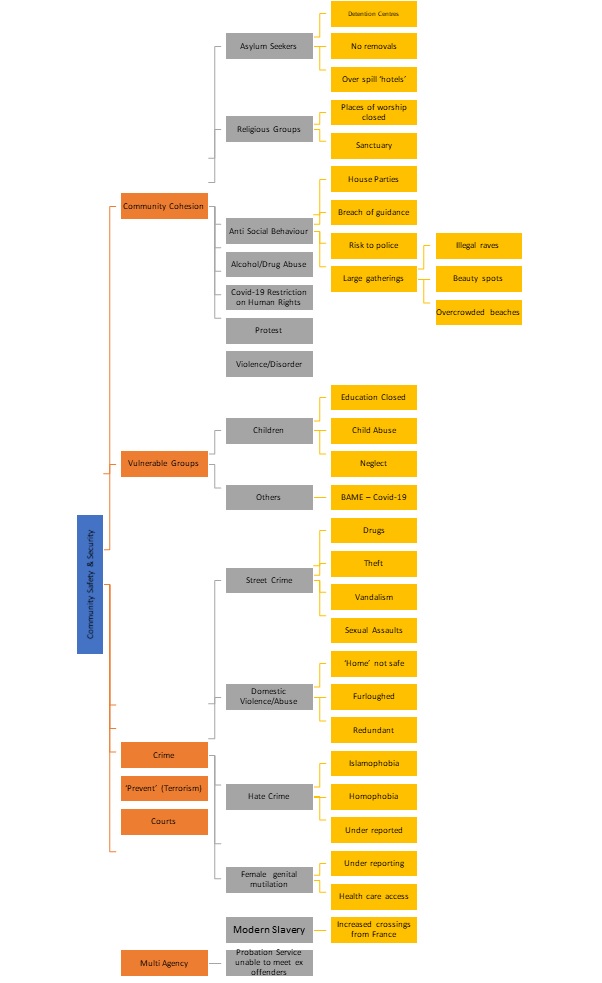

The negative effects on community safety and security from the Covid-19 crisis are difficult to quantify. Community cohesion has also suffered and crime has increased, including street crime, domestic violence or abuse, hate crime, female genital mutilation and modern slavery. See the impact tree analysis below.

The impact on police resources since March has been immense. Requirements of senior officers to consider and manage the health, safety and security of staff, sickness, welfare, testing and the training or education both of recruits and internally have been cancelled or delayed.

Learning the lessons

It is being widely reported that we were warned, both by the experts and by reality. Yet on most fronts, we were still caught unprepared or behind the curve. We will need to understand why and what needs to be done to prepare for the next pandemic. There is a clear need to plan for local debriefs to identify organisational learning and the inevitable public inquiry.

I have some sympathy for the current crisis leaders and feel I should acknowledge that even foreseeable problems can be inherently hard to prepare for. But we need an honest appraisal of why we couldn’t grasp the scale of the threat.

The UK Emergency Response and Recovery provides guidance for all agencies at (4.6.) Identifying and learning lessons, the key themes are:

6.1: Keep records to facilitate operational debriefs and evidence for enquiries. Capture information while memories are fresh

6.2: Comprehensive record of events, decisions, reasoning behind key decisions and actions taken

6.3 Identify lessons and make more widely available for those who might be involved in future emergencies

6.4: Debriefing should be open and honest

Individual and Local Debriefs

To support the public inquiry and facilitate learning, there needs to be an agreed structure to the individual agencies and local resilience forums debrief. This will require some planning and central guidance. The methodology will be important for us to identify what went well and what did not go well, and how we can use this information to improve our future preparedness, response and recovery.

The process normally starts with a summary of the event – accepting that the debrief may well reveal more information about the event, an opportunity for individuals to reflect on their role in the event, an opportunity for open discussion and a facilitated plenary discussion, perhaps on key issues emerging.

In order to identify the post-event organisational learning, the facilitator needs to create a single debrief report, analysis of where the response was effective and where it was not, consider whether any general or specific review activity is required as well as identify ways in which the response could have been improved. Then action plans should be developed.

It is easy to identify lessons, but for organisations to learn them they need to change plans, training and exercising. In a report commissioned by the Cabinet Office Civil Contingencies Secretariat, Dr Kevin Pollock consistently found the same or similar issues raised by the 32 inquiries and events he examined, covering the years 1986 to 2010.

This was identified as a “cause for concern” and Pollock suggests that “lessons identified” from the events are not being learned to the extent that there is sufficient change in both policy and procedure to prevent repetition.

How can we ensure the lessons identified become lessons learned for pandemic events? It will require a commitment from central government and politicians, monitoring and auditing the process to ensure that the resilience programme is being followed and all recommendations pursued to conclusion.

The current Covid-19 crisis presents a significant challenge for the entire world. Understandably, the current focus of governments and organisations tends to be on the response to rather than the recovery from the crisis. This focus will need to change if organisations want to achieve a return to normality and a sustainable resilience.

Image: milkos/123rf

Roger Gomm, 10/12/2020