Covid-19: Evidence of ‘what works’ in an effective multi-agency response,

Part II

This is the second in a series of ongoing reports that aim to understand the current challenges faced by Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) during the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK.

The goal is to support the ongoing development of good working practice. An introductory report, including background information, introduction to relevant theory and overview of the methodology, as well as a first report discussing findings from interviews conducted between April 13, 2020 – May 14, 2020.

Through ongoing interviews with responders at the strategic and tactical response levels, the research summarised here addresses interoperability dynamics at both the local and national level and assesses how the evolving situation affects strategies, practices and outcomes over time.

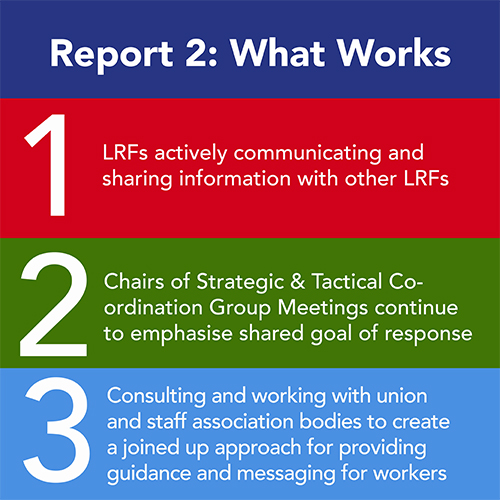

The findings from the interviews are presented alongside relevant theory to generate evidence and theory-based suggestions of ‘what works’ in the Covid-19 response. We identify three key findings, which are discussed in order, followed by the three ‘what works’ suggestions.

Key findings

-

Importance of active communication between LRFs

-

Importance of maintaining a shared identity within the LRF

-

Importance of a joined-up approach between management and union bodies/staff associations

Method

Interviews included in this report (n=16) were conducted with 10 different responders, five of whom were included in the first report. Interviews took place between May 15 – June 12, 2020. During this period, response activities included revisiting capabilities stood up previously, and looking for what can be removed or stood down, for example mortality planning, Pandemic Multi-Agency Response Teams (PMART), and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) management. Activities have also included preparing for a potential subsequent wave and managing a return to business as usual.

Context

-

On May 13, 2020: Some lockdown measures were eased in England, allowing people to spend more time outside and meet one person from another household while adhering to social distancing rules.

-

On May 19, 2020: Lockdown measures were eased further in England with groups of six people from different households being allowed to meet, while adhering to social distancing rules.

-

On May 29, 2020: Lockdown measures were eased further in Scotland, with groups of up to eight people from two households being allowed to meet, while adhering to social distancing rules.

-

On June 1, 2020: Lockdown measures were eased further in England with groups of six people from different households being allowed to meet outside, while adhering to social distancing rules; and lockdown measures were eased in Wales, with members of two households being allowed to meet, while adhering to social distancing rules.

-

On June 8, 2020: Rules requiring travellers arriving into the UK to quarantine for 14 days were introduced.

-

Importance of active communication between Local Resilience Forums

Results from interviews

In our first report, a key challenge highlighted by responders was centred on communication between national and local level bodies. Although this challenge still seems to be present, there now seems to be a shift in the way some LRFs are managing it, with one responder noting: “While national input would be helpful, it’s not essential because we will still respond.” Another commented: “In the absence of information from government, we will put an interim decision in place because we have to do something”. Within Wales, a respondent said: “We are now having to ask officers to use common sense (when enforcing legislation).” This is because: “Legislation is being interpreted by different police forces very differently.”

One responder described that the arrangements with government: “Are maturing at both ends, we as a partnership, Strategic Coordination Group (SGG) and LRF are now accepting, and at peace, with some of the things you can expect from central government.”

This responder expanded further: “The relationship (with government) has improved a lot, because we understand it now and understand that it’s not just clumsiness, or lack of attention or care, it is the fact it cannot be done,” and described how: “We are now solving the same problem, but in a different way.” This LRF has tried to mitigate for the communication challenges by forming connections with other LRFs at a regional level: “Rather than keep asking things from the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), we have agreed a common approach across the South East (…) this has enabled us to start comparing, and at the same time we have written to Cabinet Office Briefing Rooms (COBR) and SAGE, saying: ‘This is our interpretation of the data, are we wrong?’ rather than, ‘tell us what you know’.”

Another member of the same LRF explained that this regional co-ordination came about through pre-existing relationships with personnel from other regions and described the benefits of this: “We have a regional Tactical Co-ordination Group (TGG) catch up to discuss what each other are doing and sharing what is going well. It is an opportunity (…) to discuss what each other are looking at.”

A key example of the benefit this regional connection provided was when a member of a different LRF in the same region informed them that testers had been approached by a member of the media and had been offered £2,000 to get a photo of two police officers standing within two metres of each other. The responder described how: “We were able to take this and feed it back into our region and get the comms (communications) out there so that everyone was aware that there were people like this out there. As police officers, this isn’t unexpected, but for some of the partners around the table, it came as a bit of a shock that the press would do that.”

Similarly, a representative from the Scottish Ambulance Service discussed the strong international links that were helping to inform the service’s response: “We have had relationships with Australians, Scandinavians and the North Americans for six or seven years around other projects, so already have strong working relationships internationally.”, The respondent explained: “We have been learning lessons off each other.”

The respondent is also working closely with London Ambulance Service: “When London was getting hit about three to four weeks ahead of us, I had a number of one-to-one strategic meeting calls with other strategic commanders in London about how does this feel; (it was) not about numbers, but the phone a friend item – how is it going, what does it feel like?”

This ‘lesson sharing’ seems to be echoed among responders in the London Fire Brigade who described sharing their lessons with the National Fire Chiefs Council: “Other fire services who are perhaps getting some of the same issues now can take a lot of learning from London Fire Brigade.”

Importance of maintaining a shared identity within the Local Resilience Forum

Results from interviews

Previously, responders highlighted that a key strength of the response was the ability of partners from different agencies to come together effectively. However, a concern now raised by some responders is the pressures on the LRF partnership as business as usual starts coming into play. One responder said: “A danger in any incident is that you get a very high level of energy build up, then get a stabilisation and then almost the danger comes when people start to slacken off and make mistakes and a general laziness about it, because people are tired, and at that same time we have EU Exit coming back in”.

Another responder expanded on this and explained: “It takes an external threat for everyone to come together and work for the greater good and taking one for the team, even if it doesn’t necessarily sit with you. But as soon as that external threat slightly dissipates, even if it is just that we are over the initial peak, everyone starts petty squabbling and it unravels from the top.”

“Conflicts” and “tensions” have been observed beginning to emerge in some LRFs. For example, one responder described how: “There are conflicting pressures that are arising. For example (we have) still got a lot of work to do post Grenfell. We are trying to assess what work that has previously been stalled because of Covid and what we can start bringing back and what resources that would require.”

Furthermore, another responder commented: “Tensions have been caused when people are trying to do what is right for their organisation, but not necessarily seeing what is right for the overall.” The responder noted: “There seems to be a reluctance in some people to question or seek understanding about an area they think their organisation has nothing to do with.”

An example of this was provided by another responder who explained: “The 14-day quarantine period after going abroad has raised angst among SCG members.” This responder continued: “There is still the team ethos that there has been from the beginning, but people are getting their agency head back on now (…) own agency is now coming back into the partnership, at the beginning, the key drive was to survive Covid-19 and support the NHS and when we have those clear guides and simple messages, it makes it easy for everyone to be on board. No one is trying to be awkward but, as more of own agencies and employer issues come to light, we start to get debates which doesn’t involve everyone, whereas at the beginning everyone was involved”.

However, a responder in London described how: “(Our) own agency work isn’t having too much of an effect on the partnership working because the partnership working was already embedded, what we are doing is what we already do, but bigger.” Another responder from a different region said that although other business is returning: “We work hard for each other, because we like each other and trust each other, and we know each other’s issues and we have a trust relationship whereby we can have open conversations. We are committed to each other to develop these relationships, which will put us in good stead for the future.”

This challenge also does not seem to be as prevalent in Scotland, with one responder describing how: “We don’t have commissioning (the process of procuring health services, 3) in Scotland, so we don’t have that competitive side of things, which there has been previously. It means we are all on the same team 99 per cent of the time anyway, so there is a definite feeling in Scotland that we are all in this together. The teamwork in Covid has been fantastic.”

Importance of a joined-up approach between management and union bodies

Results from interviews

A further challenge discussed by some responders is around engagement with staff associations and union bodies. For example a representative from the Ambulance Service stated: “What was very unhelpful was some organisations (…) putting guidance out on aerosol generating procedures, which was different to Public Health England (PHE) and Health Protection Scotland advice, which isn’t helpful when you are a paramedic who has (…) a professional body you hold in high esteem saying one thing, and then PHE saying something differently.”

Similarly, a responder from the Fire and Rescue Service (FRS) highlighted that: “An ongoing challenge is around the levels of PPE and the face masks versus face coverings. This is a challenge because we have got to put something in place that is manageable, but agreed across the rep (representative) bodies and expectations can sometimes be unrealistic, so it is about doing what we can to the best of our abilities rather than shutting things down because staff think it is unsafe.”

This responder further highlighted how the situation was made even more challenging because: “The guidance comes down to individual translation of what the guidance means, for example the employer might have a different translation of what the guidance means compared to the employee.” This responder recognised that: “No one is being deliberately obstructive, but it is about understanding what the government guidance is and there has been conflicting advice and it isn’t black and white.” Emphasising that this is challenging, the same responder noted: “We always need to make sure we meet the guidance, because if we don’t meet guidance the union can deter its members from undertaking certain roles or tasks.”

To try to overcome this challenge, this responder described how: “Instead of the fire brigade as the employer reaching an impasse with the rep bodies over a piece of Covid-19 guidance, it has taken neutral expert advice from PHE. We can now go to the union with something that has showed that we have tried to listen to them and come up with a safe system of work.”

In contrast, this challenge does not seem be shared with the Police Service, which is unionised in the same way as the FRS and Ambulance Service. While police staff (ie not warranted officers) have representative unions (Unite and Unison) and can be called on to strike, the Police Service (warranted officers) cannot strike, as stated in the 1919 Police Act. Instead, they have the Police Federation (a staff association) which is constituted differently to union bodies. The Police Federation negotiates on behalf of staff for pay and welfare, as well as having a highly effective route to the Home Secretary and media.

One responder explained: “We had early engagement with staff associations to make sure we have them on board, because without them supporting our message, ensuring their members were getting the right information through to them, we would’ve had a much harder struggle.” The responder continued: “We engaged with all three (Unite, Unison and the Police Federation) early on to ensure that there was good communication links, a single message to all and a genuine desire to minimise the risks to colleagues.” The responder described how this has been beneficial because: “By them (unions and staff associations) supporting our message, it adds a lot of credibility to what we are saying, more so if it was just coming from a central point.”

Theoretical application

As discussed previously, the current Covid-19 response involves interactions between a number of different groups including (but not limited to) members of the public, local responder organisations and national government agencies. Within each of these broader groups, there are subgroups (for example, responders from response organisations) (1).

The Social Identity Approach is useful for understanding these dynamic relationships and how they change and develop over time. Social identity refers to group membership that an individual internalises and that helps define their sense of who they are in a particular context (4). In other words, individuals can see themselves as ‘we’ as well as ‘I’. When there is a strong sense of “we” within a group this can help the group to work more effectively together (5, 6), and fosters trust in other group members (7).

There are three key factors that explain how shared social identity can arise. Firstly, if a group membership has been important to an individual previously, they are more likely to see themselves as part of the group in the future (8). In this context, responders might be more able to identify with other partners in the LRF if they have had previous working relationships with them, perhaps through previous responses, or training.

Secondly, identification with the group must be meaningful in the situation (9). For example, those responding to the Covid-19 pandemic are more likely to identify with other partners in the LRF if they perceive that others have a shared understanding with them on what they are doing, why they are doing it, and if they share the same goals.

Finally, the way that others in the group define each other is important in helping to shape the way an individual in the group defines themselves (10). Leaders are particularly important in this sense as their ability to represent the group and embed a sense of ‘we-ness’ between members of the group can help strengthen the shared identity between members and secure the support of others (11).

In the current response to the pandemic, the chairs of the SCG and TCG meetings could play an important role in helping to enhance that sense of ‘we-ness’ within the group and strengthening group efficacy through inclusive initiatives and the language they use (for example, ‘we’, ‘us’ rather than ‘you’). However, if leaders’ actions are perceived to be in conflict with union bodies, who are representatives of the workers, workers are less likely to trust their leaders (12) and shared identity between workers and their leaders is likely to decrease.

Evidence and theory-based suggestions of ‘what works’ in the Covid-19 response

-

Louise Davidson,Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science & Technology, Health Protection Directorate, Public Health England, United Kingdom

-

Holly Carter, Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science & Technology, Health Protection Directorate, Public Health England

-

John Drury, School of Psychology, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

-

Richard Amlôt, Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science & Technology, Health Protection Directorate, Public Health England, UK

-

Alexander Haslam, School of Psychology, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia

-

Clifford Stott, School of Psychology, University of Keele, Staffordshire, United Kingdom

John Drury, Holly Carter and Clifford Stott were supported by a grant from UKRI, reference ES/T007249/1.

Holly Carter and Richard Amlôt are funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response (EPR) at King’s College London in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with the University of East Anglia and Newcastle University.

Louise Davidson is also affiliated to the EPR HPRU and her PhD research is jointly funded by the Fire Service Research and Training Trust and the University of Sussex.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England.

References

Davidson, L, Carter, H, Drury, J, Amlôt, R, Haslam, S A & Stott, C (2020): Covid-19: Recommendations to promote an effective multi-agency response. Retrieved from: https://www.crisis-response.com/comment/blogpost.php?post=569

Davidson, L, Carter, H, Drury, J, Amlôt, R, Haslam, S A & Stott, C (2020): Covid-19: Recommendations to improve effective multi-agency response, Part 1. Retrieved from https://www.crisis-response.com/comment/blogpost.php?post=570

NHS (2015): Commissioning: What’s the big deal. Retrieved from: https://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/thenhs/about/Documents/Commissioning-FINAL-2015.pdf

Turner, J C (1982): Towards a redefinition of the social group, In H. Tajfel (Ed), Social identity and intergroup relations (pp. 15-40), Cambridge University Press

Drury, J, Cocking, C. & Reicher, S (2009): The nature of collective resilience: survivor reactions to the 2005 London bombings. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 27(1), 66 – 95.

Haslam, S A, Jetten, J, & Waghorn, C (2009): Social identification, stress and citizenship in teams: a five-phase longitudinal study, Stress and Health, 25(1), 21-30, doi: 10.1002/smi.1221

Turner, J C, Hogg, M A, Oakes, P J, Reicher, S D, & Wetherell, M S (1987): Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory, Basil Blackwell.

Oakes, P J, Haslam, S A, & Turner, J C (1994): Stereotyping and social reality, Blackwell Publishing

Haslam, S A, & Turner, J C (1992): Context-dependent variation in social stereotyping 2: The relationship between frame of reference, self-categorization and accentuation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 22, 251-277

Reicher, S D, Haslam, S A, & Hopkins, N (2005): Social identity and the dynamics of leadership: Leaders and followers as collaborative agents in the transformation of social reality. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 547-568

Steffens, N K, Haslam, S A, Reicher, S D, Platow, M J, Fransen, K, Yang, J, Jetten, J, Ryan, M. K., Peters, K. O., & Boen, F. (2014). Leadership as social identity management: Introducing the Identity Leadership Inventory (ILI) to assess and validate a four-dimensional model. The Leadership Quarterly, 25, 1001-1024.

Holland, P., Cooper, B. K., Pyman, A., & Teicher, J. (2012). Trust in management: the role of employee voice arrangements and perceived managerial opposition to unions. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4). doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12002

Louise Davidson, 01/06/2020