The slowing Gulf Stream

March 2021: A recent study carried out by scientists in Ireland, Britain and Germany suggests that the Gulf Stream is at its weakest for a thousand years. If the current slows down enough, there will be a ‘tipping point’ of no return when it could disappear altogether, say the researchers. This could have consequences for both sides of the Atlantic, with noticeable effects on weather patterns and sea levels.

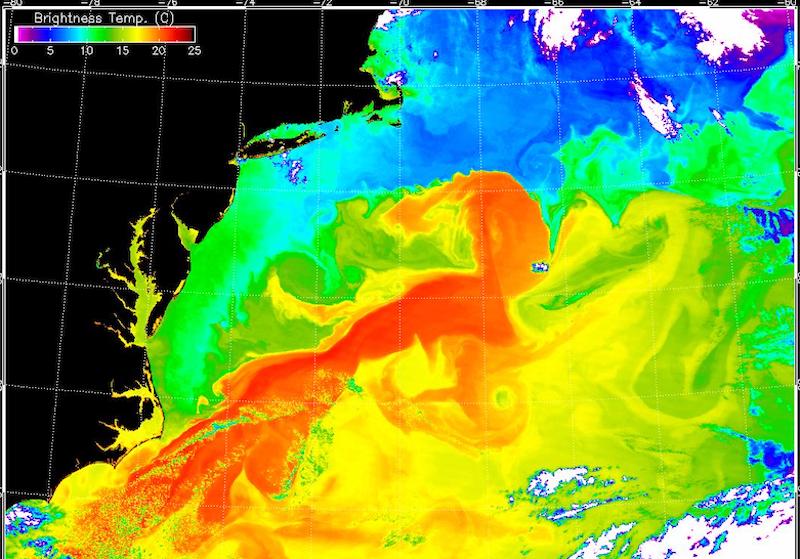

The red pixels in the image show the warmer areas approaching 25°C, greens are intermediate values from 12 – 13°C and blues are relatively low values of less than 10°C. Image credit: Nasa Earth Observatory (2001, cropped)

The study’s lead author, Levke Caesar, a climatologist from Maynooth University in Ireland, suggests that the tipping point could be reached as soon as 2100 if global warming continues on its current trajectory, as the strength of the current could diminish by as much as 45 per cent.

"The Gulf Stream System works like a giant conveyor belt, carrying warm surface water from the equator up north, and sending cold, low-salinity deep water back down south. It moves nearly 20 million cubic metres of water per second, almost 100 times the Amazon flow," explains Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research PIK, initiator of the study to be published in Nature Geoscience.

The Gulf Stream, also known as the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) keeps temperatures in Florida and the UK mild, it influences the path and strength of cyclones and helps to regulate sea levels.

Since direct AMOC measurements only began in 2004, the researchers used comprehensive proxy data – including information from historical data, such as ships logs and from environmental archives including data from tree rings and ice cores – to build up a perspective of the AMOC’s speed over time. The robustness of the data was then tested rigorously.

"For the first time, we have combined a range of previous studies and found they provide a consistent picture of the AMOC evolution over the past 1,600 years," says Rahmstorf. "The study results suggest that it has been relatively stable until the late 19th century. With the end of the little ice age in about 1850, the ocean currents began to decline, with a second, more drastic decline following since the mid-20th century." In 2019 the special report on the oceans of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded with medium confidence: "The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) has weakened relative to 1850-1900."

The effects of global warming could be responsible as melting ice sheets and increased annual rainfall dump fresh water into the North Atlantic, reducing its salinity and density at the northern end of the Gulf Stream. According to the researchers, this freshwater inhibits how quickly the water can sink and begin its journey back south, weakening the overall flow of the AMOC.

Its weakening has also been linked to a unique substantial cooling of the northern Atlantic over the past hundred years. This ‘cold blob’ was predicted by climate models as a result of a weakening AMOC, which transports less heat into this region. "If we continue to drive global warming, the Gulf Stream System will weaken further—by 34 to 45 per cent by 2100, according to the latest generation of climate models," concludes Rahmstorf.

This could bring us dangerously close to the tipping point at which the flow becomes unstable and potentially stops altogether.