Long term woes of displaced Afghans in Pakistan

As reported in our CRJ blog of August 2015, the authorities in Pakistan’s Capital of Islamabad have begun a drive against 42 slum areas in the city, writes Luavut Zahid. Here, she looks at the harsh conditions experienced by Afghan refugees who live in the 1-12 area.

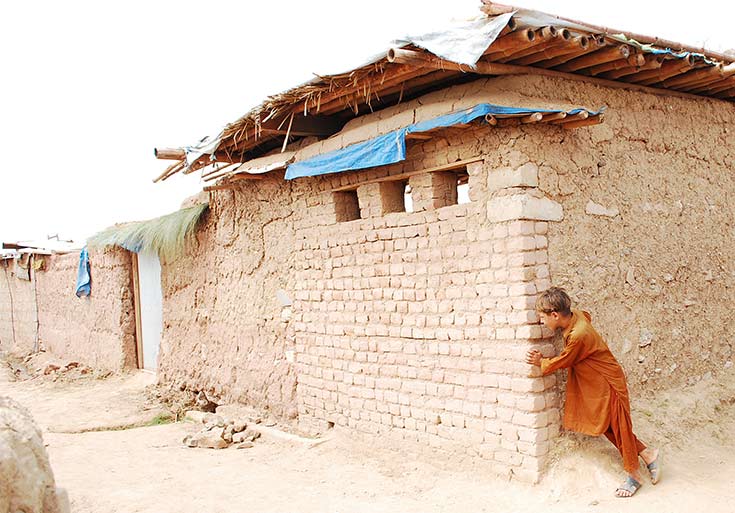

The Hashoo Foundation (HF) has been implementing a project for the Afghan Refugees residing in 1-12 Islamabad who were deprived of the basic needs of life. Hashoo Foundation, with the support of the UNHCR and Gesellshaft Technische Zusamenarbeit (GTZ), has been able to establish two basic health units for males and females, initiate primary education system for the children and equip young people with some marketable skills such as tailoring, embroidery, motor winding and electrician. Yet conditions remain exceptionally tough for residents of the area, and their future is uncertain (photo: Hashoo Foundation)

The Capital Development Authority (CDA) tore down the 1-11 slum, popularly known as ‘Afghan Basti’. The notion that any Afghans live in the area itself is a myth and the area consisted predominantly of Pakistani Pashtuns because it was flattened down.

The popular, yet false, rhetoric surrounding the slum gives the impression that it was a den of both documented and undocumented Afghans, which was cited as ample reason for the area to be torn down by the CDA.

While it is true that some Afghans did dwell in the 1-11 area, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR) moved them out to sector 1-12 area under an unofficial agreement with the authorities in 2009.

A source from within the CDA’s recent drive against slums anonymously told me that the situation is indeed dire for the documented refugees living in the 1-12 area. “We are talking to the UNHCR’s representatives and this place will most certainly be taken care of. We will move whenever we get the order,” the source said.

The CDA is unwilling to take any other role except for the demolitions it has planned. “We aren’t concerned about their relocation, that’s the UNCHR’s prerogative and they will do what they need to do. Where they are going to go? We don’t know,” the source added.

Refugees, some of whom have been displaced for 37 years - and many of whom were born in the camps - feel alienated and confused about their future. Some told the author that they don't have access to medical or educational facilities (photo: Luavut Zahid)

UNCHR’s Communication and Public Information Officer, Duniya Aslam Khan, said that the organisation was looking at alternatives for the refugees.

“Our understanding with them was that when the 2009 evictions happened in 1-11 they were offered the 1-12 plot temporarily. If all slums are being targeted then it’s not possible that they would be left alone to live there,” she said.

“We are working on a plan to see what is the best option for them in case they are given an eviction notice or there is an operation against them,” she added.

While the fate of the slums in 1-12 hangs in the balance, the refugees who dwell there can’t help but feel uneasy. The inevitable evictions are the least of their problems as things stand.

Pakistan’s capital plays host to a number of Afghan refugee families. Recent drives to push refugee populations back into the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, with the intention of eventual relocation into Afghanistan, has reduced the numbers considerably. However, many still remain.

The 1-12 sector is one such area. As per UNHCR estimates, the area provides a temporary shelter for over 500 registered families, made up of almost 3,500 men, women and children. It can be seen as a case study for other camps in Pakistan; many are distressed by mirror issues and similar fears.

Pakistan’s terrorist problem has begun to intersect with its refugee problem. Of late a police crackdown has been increasingly targeting Afghan refugees and Pakistan has honed in on its refugee problem in the context of the wider security issues that plague it.

Men in the area told me that the police have been taking one to two men into custody over what they claim is suspicious activity every single day. Ever since the crackdown on terrorism began in Pakistan, the average terrorist has been profiled as a Pushtoon. Times are not just tough for Afghan Pashtuns, but for Pakistan’s own tribal people as well. Action against ‘suspicious’ men and women almost always translates into arrests at camps like the one at 1-12.

Aziz, a man in the area, originally belongs to Kandahar, but doesn’t want to leave despite the plethora of problems plaguing him and his family.

That is despite the fact that a labourer living in the area will typically only earn around Rs 200-300 (approximately two to three US dollars) on an average day. Men from the 1-12 area said that they were often stopped while at work, or on their way home, and harassed for money by police officer.

But skirmishes with the law are the least of their problems, they claimed.

“There is no water here. We had one pump to bore water and that broke down a few months ago. We have no electricity here. We use second hand solar panels to power two fans – but you know the sun doesn’t shine all the time in Islamabad,” said one.

While water and power are making life harder, health and education are faring no better.

“The school is too far away… even if we could send them every day they won’t let our children in because we’re Afghanis,” Khalil, another dweller in the 1-12 area said.

He pointed out that a school was indeed established in the area but it couldn’t last more than a few weeks. “There was no one to run it or take care of it properly. The teacher would show up for 30 minutes and then leave without doing much. Even that school was only for the little ones, there is nothing for the bigger children,” he said.

Many children are getting their education from a madrassas nearby instead of a school. “Only a handful people have fewer than 10 children here. Even if they gave us admissions we can’t afford the luxury of education for them,” Khalil said.

The refugees feel alienated and confused when they go to hospitals in the capital.

“There is no medicine for Pashtuns. We don’t understand what language they are speaking in. If they want to give us medicine they do so in the name of god as though it’s for charity and then tell us to go away,” an elder from the area said.

“We can’t afford multiple medicines or doctors so we take what we can get and come back. If we try to ask questions we are told to be quiet. It feels as though the doctors want to get rid of us as soon as possible,” he added.

Society for Human Rights and Prisoners' Aid (SHARP) Director Sheraz Khan has been working with Afghan refugees since 2001. The organisation works in collaboration with the UNHCR and has operations that cover all of Pakistan.

Khan pointed out that the issues being faced by the 1-12 dwellers are not happening in a vacuum, and that such problems can be found in most Afghan refugee village camps around Pakistan.

The refugee village camps are running out of resources. Education centres have shut down after funding and aid began to dwindle, and the same is occurring with medical centres. Such accessibility issues are being faced by numerous refugees around Pakistan.

The SHARP director pointed out the changing burden of refugees in the world: “Within the last few years the UNCHR was facilitating health and education, but there are several refugee crises looming globally now, and funding isn’t as readily available because it is being diverted to other places, like Syria for instance,” he told me.

“The refugees have been here since 37 years. Since 2009 there has been displacement of people all over Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which houses most of the refugee village camps; so even locally the government doesn’t have the funds to spare,” Sheraz explained.

In terms of government schools the Afghans do not rank high in terms of priority. “Pakistan has limited resources and Islamabad has its own influx of internally displaced people. They will be facilitated first if there is space in schools,” Sheraz said.

The problem is very real. The war against terrorism displaced hundreds of families all over the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Known as Internally Displaced People (IDPs) or Temporarily Displaced People, Pushtoons are now living in situations similar to those of the refugees.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, over 20-30 per cent of the enrolled students are Afghanis, but the priority remains to ensure that Pakistani children get seats first.

“Generally, if the refugees meet the criteria and provided that the resources are available their children will get admissions into schools,” he said. However, considering Pakistan is tackling its own education emergency, finding these resources can be tricky.

Moreover, resources aren’t the only roadblock to education.

“You won’t find any of them in our colleges. That is because the intermediate board comes into play and that enrollment requires approval from the Afghan embassy, which creates problems,” he said.

It is indeed telling that despite all their troubles and irrespective of how the situation is worsening for these refugees, they continue to want to stay in Pakistan.

“I was born here. I have lived here my whole life. My children were born here. I don’t know what to do if you force me to return. I have been arrested twice for having a fruit stall, I am not a terrorist, you are friends with the real terrorists,” Aziz said.

“Sending me to Afghanistan is like sending me to an alien place. I don’t know it,” he added.

“Most of us are afraid we will get killed if we go back. Even now the elders want to return but the young people – the ones born here – don’t want to go back,” Khan, another dweller, said.

“If they send me back to Afghanistan I will try to go to Iran. There’s nothing for us to do back there,” he added as Aziz nodded in agreement.

In essence the problem isn’t just the lack of facilities or the demonisation of the Pushtoon ethnicity. The problem for many Afghan refugees is that they know nothing of Afghanistan. If and when the authorities get around to moving this lot back to Afghanistan, as it has been doing with refugees in other camps, the options for them will remain limited.

Luavut Zahid is a professional journalist based in Lahore and is CRJ's correspondent in Pakistan. She blogs and curates blogs for CRJ on security and humanitarian issues in Pakistan

Luavut Zahid, 14/03/2016